History of gaming

Tribal nations governed themselves and provided for their people long before the United States of America existed. The U.S. Constitution (Article 1, Section 8) recognizes tribal nations as sovereign governments that maintain the power to determine their own governance, pass and enforce laws, and provide programs and services on its lands.

Tribal gaming, as we know it today, dates back many years. However, the governmental sovereign status of tribal nations is at the heart of nearly every modern-day debate surrounding gaming.

The story of Minnesota's Indian gaming compacts

In 1988, Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA), proclaiming that tribes must be the “sole owner and primary beneficiary” of Indian gaming activities.

The State of Minnesota believed that tribal gaming could benefit rural communities that have often struggled with economic development. Minnesota tribes were the first in the nation to negotiate and sign gaming compacts with a state government.

The Path to Indian Gaming

Tribal sovereignty

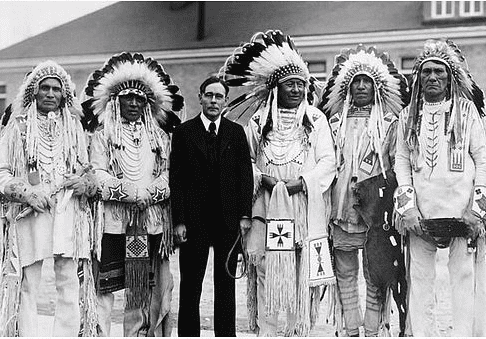

The U.S. Constitution, which was adopted in 1789, specifically recognizes the sovereignty of Indian nations, along with foreign nations and the “several states.” This means that Indian tribes are equal to, not subservient to, states and foreign nations.

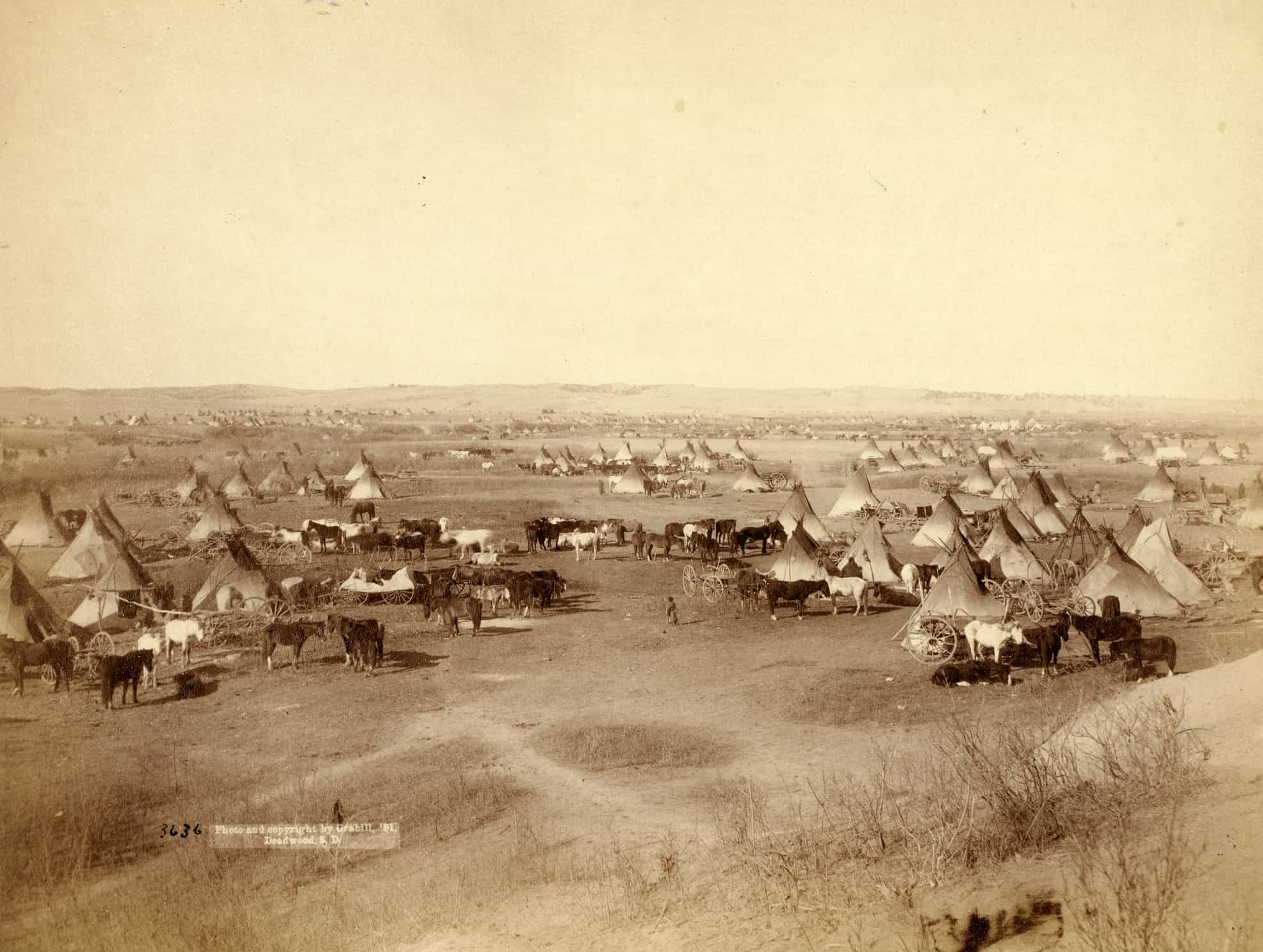

From the 1770s to the late 1800s, Indian tribes signed treaties under which they gave up much of their land to the federal government. However, under these agreements, the tribes retained the right to govern themselves as sovereign nations. In this context, the word “retained” is very important, because it reflects that tribes never gave up the right to govern themselves, even when they were forced to surrender their land. This is an important legal distinction, and explains why tribal sovereignty is known as an “inherent” right rather than a right that has been conferred or granted by others.

Supreme Court precedent

The U.S. Supreme Court consistently has upheld the principle of tribal sovereignty. In 1832, the Supreme Court ruled in Worcester v. Georgia that Indian tribes are “distinct political communities, retaining their original rights as the undisputed possessors of the soil from time immemorial…the very term nation, so generally applied to them, means of people distinct from others, having territorial boundaries, within which their authority is exclusive, and having a right to all the lands within those boundaries, which is not only acknowledged but guaranteed by the United States.”

The U.S. Supreme Court consistently has upheld the principle of tribal sovereignty. In 1832, the Supreme Court ruled in Worcester v. Georgia that Indian tribes are “distinct political communities, retaining their original rights as the undisputed possessors of the soil from time immemorial…the very term nation, so generally applied to them, means of people distinct from others, having territorial boundaries, within which their authority is exclusive, and having a right to all the lands within those boundaries, which is not only acknowledged but guaranteed by the United States.”

Assimilation and allotment

Federal policy toward tribal governments and American Indians has been inconsistent. From 1870-1934, federal officials tried to force Indian people to assimilate into mainstream American society. Many Indian children were seized from their homes and forced into boarding schools, where they were forbidden to wear their traditional clothing, speak their own language or have contact with their families. This era was also characterized by the illegal seizure of tribal lands.

Federal policy toward tribal governments and American Indians has been inconsistent. From 1870-1934, federal officials tried to force Indian people to assimilate into mainstream American society. Many Indian children were seized from their homes and forced into boarding schools, where they were forbidden to wear their traditional clothing, speak their own language or have contact with their families. This era was also characterized by the illegal seizure of tribal lands.

In order to accommodate westward settlement, Congress passed the Dawes Act of 1887, permitting the allotment of Indian land to non-Indian people. Millions of acres were transferred illegally from tribes into private ownership. Before 1887, tribes across the country still held about 138 million acres of land. By 1934, this amount had been reduced to less than 48 million acres. They were left with the least desirable land, inadequate for hunting, fishing, farming, grazing or other activities that might sustain a community. Many tribes lost the heart of their homelands; some were forced into virtual extinction.

Reorganization and recognition

Acknowledging the failure of previous approaches, the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. The IRA reaffirmed Congressional recognition of tribal sovereignty, ended the allotment policy, restored some tribal lands, and encouraged tribes to reorganize and establish constitutions for the purposes of self-government. Many tribes returned to what was left of their homelands, adopted constitutions and were duly recognized by the federal government. Other tribes won recognition later, usually by acts of Congress passed specifically to address each tribe’s unique history and situation.

Termination and relocation

In 1951, federal policy changed again. The U.S. government decided to neglect its long-recognized trust responsibility to tribes, including promised services such as health and education. During this period, the government also enacted a relocation program, promising tribal members jobs and assistance if they moved to urban areas. Such assistance never materialized, and thousands of Indian people who moved off the reservation were left stranded without family, jobs, education or hope. The termination of federal programs and the migration of Indians into urban centers were devastating to tribes and the nation’s Indian reservations, where impoverished conditions continued to worsen.

In 1951, federal policy changed again. The U.S. government decided to neglect its long-recognized trust responsibility to tribes, including promised services such as health and education. During this period, the government also enacted a relocation program, promising tribal members jobs and assistance if they moved to urban areas. Such assistance never materialized, and thousands of Indian people who moved off the reservation were left stranded without family, jobs, education or hope. The termination of federal programs and the migration of Indians into urban centers were devastating to tribes and the nation’s Indian reservations, where impoverished conditions continued to worsen.

Self-determination

By 1973, Congress realized that drastic changes were needed if American Indians were to survive. The Indian Self-Determination Act was a significant turning point in U.S. policy, restoring funding for Indian programs and services, and authorizing tribes to run them. It also gave tribes more influence over the priorities set by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and mandated that tribes be consulted regarding policy changes that would affect them.

By 1973, Congress realized that drastic changes were needed if American Indians were to survive. The Indian Self-Determination Act was a significant turning point in U.S. policy, restoring funding for Indian programs and services, and authorizing tribes to run them. It also gave tribes more influence over the priorities set by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and mandated that tribes be consulted regarding policy changes that would affect them.

Congressional support

From the 1970s-1990s, Congress enacted several key pieces of legislation to strengthen tribal sovereignty and reaffirm the right of tribal self-governance:

From the 1970s-1990s, Congress enacted several key pieces of legislation to strengthen tribal sovereignty and reaffirm the right of tribal self-governance:

- Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968: applied most of the Bill of Rights requirements and guarantees to tribal governments.

- Indian Self-Determination and Education Act of 1973: affirmed Congressional policy that tribal governments should be permitted to control education programs, contracts and grants affecting their own people.

- Indian Health Care Improvement Act of 1976: made health care for Native communities a higher federal priority, and gave tribes greater control over the way in which health care services were provided on tribal lands.

- Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978: established federal rules to ensure that Indian children removed from their homes are placed with Indian families whenever possible, in order to preserve cultural values.

- Indian Tribal Justice Act of 1993: reaffirmed federal responsibility to tribal governments, including the protection of tribal sovereignty. It also reaffirmed that Congress recognizes the self-determination, self-reliance and inherent sovereignty of Indian tribes.

California v. Cabazon decision

Public Law 280, passed in 1953, gives certain states (including Minnesota) limited jurisdiction over specified areas of Indian Country. This law authorizes states to enforce state criminal laws on reservations, but withholds authority from states to enforce civil or regulatory laws on tribal lands.

This distinction became important in 1987, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians that tribes have the inherent right as sovereign governments to conduct gaming on tribal lands as long as state law does not criminally prohibit gaming activities. In states where lotteries, charitable gambling, poker and card games, casino nights, or other gambling activities were legal, tribes were free to conduct and regulate their own gambling activities without state interference.

This decision recognized that tribes have the legal authority to open casinos. State leaders responded by appealing to Congress for more power over tribal gaming within their states, which resulted in the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988.

Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA)

The IGRA gave individual states authority over tribal gaming activities and required tribes to negotiate agreements, or compacts, with their respective states in order to engage in casino-style gaming. Further, it defined three classes of Indian gaming.

- Class I: Social gaming, such as traditional Indian games played as part of tribal ceremonies or celebrations. Tribes have exclusive regulatory authority over these activities.

- Class II: Bingo, pull tabs and similar games, including non-banked card games not prohibited by state law. Expressly excluded from Class II are banked card games, such as blackjack, and slot machines of any kind. Tribes regulate Class II games under jurisdiction of the National Indian Gaming Commission (NIGC). Ordinances regulating Class II gaming must be approved by the commission, but no tribal-state compacts are required.

- Class III: Blackjack, slot machines and other banked games of chance. Class III games are legal on tribal lands only if the games are authorized by the governing body of the tribe, located in a state that permits gaming, and conducted in compliance with a tribal-state compact.

Minnesota tribes have Class III compacts allowing them to offer blackjack and video games of chance (slot machines) in their casinos. Bingo and other unbanked games are considered Class II activities and do not require compacts.

Under IGRA, the National Indian Gaming Commission has the power to license and regulate tribal casinos and their employees, promulgate standards for casino operations, collect casino financial statements, and shut down casinos found in serious violation of federal rules.